Continue reading on DataGuidance with:

Free Member

Limited ArticlesCreate an account to continue accessing select articles, resources, and guidance notes.

Already have an account? Log in

South Africa: The approach to regulating AI compared with the EU

The complexity and rapid growth of artificial intelligence (AI) have sparked the need, globally, for legal clarity when it comes to the effective regulation of AI, and South Africa is not exempt. AI raises great concern over consumer protection but, by the same token, requires stability in the support of responsible development of AI, without governments stifling the significant value that such technology might hold for the future growth of the country. PR de Wet, Director at VDT Attorneys Inc., sets out to briefly address the current steps taken by the South African Government and role players towards carving the way to effective regulation of AI in South Africa.

Although certain legislations, such as the Protection of Personal Information Act (POPIA), the Consumer Protection Act (CPA), the Electronic Communications and Transactions Act, the Cyber Crimes Act, and the Constitution provide for certain protection mechanisms, these acts all effectively serve a different purpose and the regulation of AI does not sit at its core. Therefore, AI as a unique and fairly new phenomenon, requires specialized legislation and regulation.

The South African landscape

In the Presidential Commission Report on the Fourth Industrial Revolution (PC4IR) published in the Government Gazette on October 23, 2020, the Minister of Communications and Digital Technologies identified the development and advance of AI as a key focus area in the digital economic development strategy.

The Centre for Artificial Intelligence Research (CAIR) is a South African national research network that was founded in November 2011 as a joint research center between the University of KwaZulu-Natal and the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR). In 2015, CAIR expanded to other South African universities (which include the University of Cape Town, the University of KwaZulu-Natal, North-West University, the University of Pretoria, and Stellenbosch University), and with the CSIR playing a coordinating role, conducts foundational, directed, and applied research into various aspects of AI.

The CAIR is primarily funded by the Department of Science and Technology (DST), as part of the implementation of South Africa's ICT Research, Development and Innovation (RDI) Roadmap.

During South Africa's chairmanship of the African Union (AU), the President of South Africa (Mr. Matamela Cyril Ramaphosa) at the African Union Summit of 2020, called for a unified African regional AI approach that will serve as a 'blueprint' to guide the African member-states in developing policies and regulations related to AI as a technology tool for advancement. As a result, South Africa, in collaboration with the Smart Africa Alliance (a partnership among African countries whose goal it is to accelerate sustainable socioeconomic development on the African continent through the usage of Information and Communications Technologies and through better access to broadband services), and other member-states supported by other stakeholders such as the academia, private sector, and civil society, drafted an Artificial Intelligence Blueprint (the AI Blueprint) which was later tabled at the AU.

The purpose of the AI Blueprint was to enable or position the African continent to be a global digital economic powerhouse through the adoption of AI as a general-purpose technology of today, the future, and beyond.

On November 11, 2021, the Department of Communications and Digital Technologies published the Minister's Remarks on the Launch of Africa's AI Blueprint. Among these remarks, the Minister applauds the Blueprint: Artificial Intelligence for Africa for identifying important aspects surrounding AI with regard to development, innovation, and policy-making.

The AI Blueprint outlines several key principles, including:

- Inclusivity: Ensuring that AI development benefits all South Africans, particularly marginalized communities.

- Transparency and accountability: Advocating for clear governance structures to oversee AI implementation.

- Ethics and human rights: Prioritizing ethical considerations to prevent misuse of AI technologies, safeguarding individual rights, and promoting social justice.

This document positions South Africa as a leader in the African context, emphasizing collaboration among stakeholders, including government, academia, and industry, to foster a conducive environment for AI innovation.

The AI Blueprint defines AI as: 'any technology that enables machines to operate, emulating human capabilities to sense, comprehend and act.' Therefore, it is evident that AI is meant to serve as a simulation of the human thinking process. Its goal is to absorb and digest information, and ultimately to make a decision based on its understanding of the current information at hand, whilst being influenced by past experiences.

When humans make decisions, those decisions may often give rise to certain consequences and/or liabilities, more often in companies where these humans act for or on behalf of the companies they work for.

This notion leads to the complicated question of who is ultimately responsible for the acts and conduct of AI. More so when it is argued that AI can enhance to such a point that it possesses the capabilities to build its own AI, without any further human input.

Clarity is required for appropriate remedies, consumer protection, and accountability of corporations who build, manufacture, and design AI and its associated technologies.

Liability considerations from a South African law perspective

Two of the main objectives of the AI Blueprint are to formulate policy recommendations that aim to limit risks surrounding AI and to provide guidelines on how to develop AI in order for its potential to be harnessed. This means that a complicated balance must be struck between furthering certain needs of society, whilst simultaneously, protecting the public interest of society at large.

Generally, liability for damages is dealt with in terms of the South African Law of Delict. This means that the various elements of a delict have to be present in order for a victim to be able to claim compensation for damages suffered resulting from AI.

Such elements include conduct, wrongfulness, causation, damages, and fault, which may be in the form of intention or negligence. With the element of fault, it must be determined whether the wrongdoer is willfully and consciously acting in order to achieve a specific result and whether the wrongdoer is aware that the result that they seek to materialize is wrongful in nature or it must be determined whether a reasonable person would have foreseen the possibility that damages may result due to the wrongdoer's conduct (reasonable foreseeability).

The core elements for there to be a delict very much rely on human actions and/or capabilities. The words 'willfully,' 'consciously,' 'intent,' or 'negligence' and 'reasonable person' all require some form of human conduct, element, or capabilities that no robot or machine possesses.

Much of the debate has therefore centered around whether the creator of the technology can be held liable. The position in South Africa, for the time being, remains to be governed by the common law pertaining to delict or personality injury.

Notwithstanding the above, there are certain provisions in existing legislation that might afford broader regulatory protection and remedies, dependent on the AI application that caused the damage or the loss.

It goes beyond the scope and application of this article to discuss the various legalizations and the aspects of potential criminal liability embedded therein, however, for purposes of this article, the following provisions are worth mentioning:

The Constitution

The right to privacy is a fundamental human right found in Section 14 of the Constitution.

AI processes large sets of data containing certain information and the more data it analyzes, the more it learns. Oftentimes this process involves analyzing personal information about some people or entities. The analysis and processing of this personal information may result in the invasion of privacy.

Privacy may be infringed where personal information is acquired and/or used without the knowledge and/or will of the aggrieved person. Such acquisition can take place either in the form of intrusion or in the form of disclosure.

Consequently, it is important for operators and manufacturers of AI systems to take heed of this protected right and to ensure that the operation of such AI systems does not infringe this right in any way.

POPIA

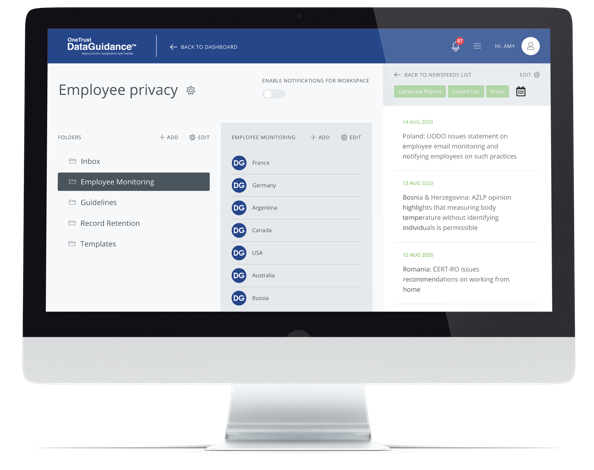

A previous article discussed the complexities of the use of AI technologies when processing personal information.

It is, however, worth mentioning that the AI Blueprint suggests that deficiencies in data protection legislation must be addressed in order to provide for the possibility of allowing AI technology to grow without enlarging the risks involved surrounding privacy infringement.

POPIA contains detailed provisions that provide for data protection regulations in South Africa. Chapter 3 of POPIA sets out the 'conditions for lawful processing of personal information.'

The processing of personal information under POPIA generally implies at least three role players, namely the data subject (person to whom the information relates), the responsible party (person who commissions the processing of personal information), and the operator (person who processes the personal information or oversees such processing if done by an AI system). In certain instances, these role players might overlap. Nonetheless, the general principle under POPIA is that it is the responsible party's responsibility to ensure that personal information is processed in a lawful manner as required by POPIA and in line with the conditions for lawful processing which are set out in Section 4: accountability; processing limitation; purpose specification; further processing limitation; information quality; and openness.

Section 5 of POPIA sets out the rights of data subjects regarding the lawful processing of their personal information. Most of these rights relate to the rights of data subjects which stem from the right to privacy contained in the Constitution. Interestingly, one of the rights found in this provision is the right of data subjects 'not to be subject, under certain circumstances, to a decision which is based solely on the basis of automated processing of his, or her or its personal information intended to provide a profile of such person,' as discussed in our previous article referred to above. This right is especially applicable in the context of AI systems.

Section 11 of POPIA sets out certain grounds for the lawful processing of personal information. Therefore, the personal information of data subjects may only be processed: where the data subject provides consent; where there is a necessity due to a contractual obligation; where the processing complies with a legal obligation; and where the processing protects a legitimate interest of the data subject; where there is necessity due to a public-law duty on a public body; or where there is necessity to protect a legitimate interest of the responsible party or a third party.

The responsible party must ensure that the AI system that processes data containing personal information in relation to data subjects does so without infringing any of the rights found in POPIA. Adherence to the conditions mentioned in POPIA will provide a guideline on how to ensure that personal information is processed in a lawful manner.

Non-compliance with the requirements of POPIA may result in penalties or even criminal liability. For more serious offenses, the maximum penalties are a ZAR 10 million (approx. $562,250) fine or imprisonment for a period not exceeding 10 years or to both a fine and such imprisonment.

For the less serious offenses, the maximum penalty would be a fine or imprisonment for a period not exceeding 12 months, or both a fine and such imprisonment.

The CPA

In terms of Section 55 of the CPA, consumers have the right to receive goods that are, inter alia, 'free of any defects.' In terms of Section 61 of the CPA, any '…producer, importer, distributor or retailer' of any product will be held liable for any damages suffered by a consumer which was caused wholly or partly because of '…a product failure, defect or hazard in any goods.'

This liability arises irrespective of whether the element of fault was present on the part of the producer, importer, etc.

Section 61 provides for joint and several liability where more than one person is found to be liable. Furthermore, certain limitations were added where the section does not apply. For example, where the defect was caused as a result of compliance with any regulation, or where the defect arose due to non-compliance on the part of the consumer with the product instructions, the manufacturer cannot be held liable for damages suffered as a result of such a defect.

In the case of Eskom Holdings Limited v Halstead-Cleak, the Supreme Court of Appeal held that in order for strict liability as provided for in Section 61 to apply, there must be 'a supplier and consumer relationship.' Where the product supplied is an AI system, Section 61 of the CPA may apply.

It is entirely possible that a defect in the programming of the AI system may arise before the system is supplied to the consumer, which defect may cause the consumer to suffer damages. In such an instance, the most problematic issue in attaining a successful claim for compensation for damages would be in proving that the defect in the AI system arose due to the actions of the supplier. Due to the ability of AI systems to learn, adapt, and essentially change their functionality, it is possible for the defect to arise during this learning process.

Furthermore, in order for Section 61 to apply, a complainant must be a consumer who suffered damages during the course of the utilization of a product supplied by a manufacturer, meaning there must be a consumer-supplier relationship present. Therefore, it is submitted that, where Section 61 does not apply, common-law delictual remedies will need to be relied upon.

Non-compliance with the requirements of the CPA may result in sanctions which include fines, imprisonment for 12 months, or in the case of private information disclosure, imprisonment for 10 years. The CPA also makes provision for administrative penalties with a maximum limit of 10% of turnover or ZAR 1 million (approx. $56,200).

The EU position

The European Parliament has adopted a resolution in 2017 to develop legislative and non-legislative policies in order to provide for liability regarding AI systems. This followed a report from the European Commission with recommendations for policy formation in this regard.

The resolution aims more at policymaking regarding liability for damages due to AI systems. However, it is submitted that the adoption of this resolution reinforces the idea that the legal regime is outdated and must be developed in order to provide for situations where damages or privacy infringement may occur due to AI systems.

These recommendations include that any duly authorized person operating an AI system who causes damages as a result of their actions should be subject to strict liability for causing said damages and where a person operates an AI system that does not pose an increased risk of causing harm, such a person should still be subjected to certain duties of care, maintenance, and monitoring.

Another recommendation suggested by the European Commission is that manufacturers of digital technologies such as AI systems should be held liable for defects in their products that arose while the product was still in the manufacturer's control.

The final important recommendation suggested by the European Commission is that it is unnecessary to assign AI systems legal personality, as damages caused by AI systems will be attributable to existing legal persons.

The European Commission takes a viewpoint that the protection of the consumer is of utmost importance. Strict liability applies in increased-risk situations and very few recommendations are suggested which may add developmental guidelines. This may be due to the fact that most European countries are developed nations with a strong increase in emerging technologies such as AI systems.

The European Commission's proposed AI Liability Directive, currently still in draft form, will work in conjunction with the EU Artificial Intelligence Act (the EU AI Act) and make it easier for anyone injured by AI-related products or services to bring civil liability claims against AI developers and users.

The EU AI Act, also currently in draft form, proposes the regulation of the use and development of AI through the adoption of a 'risk-based' approach that imposes significant restrictions on the development and use of 'high-risk' AI.

Although the current draft of the Act does not criminalize contravention of its provisions, the Act empowers authorized bodies to impose administrative fines of up to €20 million or 4% of an offending company's total worldwide annual turnover, for non-compliance with a particular AI system with any requirements or obligations under the Act.

In the UK, a government White Paper on AI regulation recognizes the need to consider which actors should be liable, but goes on to say that it is 'too soon to make decisions about liability as it is a complex, rapidly evolving issue.'

Conclusion

South Africa is a country with fewer emergences of such new technologies. The goals of the AI Blueprint aim to promote the development and use of AI in Africa to create a future increase in emerging AI systems. As such, the regulatory framework suggested by the AI Blueprint is far less restrictive in nature and aims to promote the development of AI systems in a manner that will allow the industry to grow.

The AI Blueprint suggests a combination of hard law and soft law in this endeavor to create a regulatory framework that provides protection to possible victims, but also provides room for growth on the part of the manufacturers. The areas where hard regulation is suggested are threefold.

Firstly, the software comprising the AI systems themselves should be regulated by principles of copyright/patent law. Secondly, intellectual property or privacy infringement and liability for damages should be regulated by a clearly set legal regime. Finally, existing competition laws that promote fair competition in the AI field must be applied in this context.

The possible regulatory framework for South Africa will need to provide clarity regarding the liability where the operation of AI systems may cause damages or breach the privacy of certain natural and/or legal persons. However, other regulatory systems must also be considered in order to avoid a completely restrictive framework that stagnates the important development of AI systems.

Essentially, the goal is to create a legal framework that provides protection, but that is also not excessively restrictive to encourage innovation and development surrounding AI technology in Africa. The rapid growth of AI is due to the advantageous nature of such technology and developing nations, especially African nations, will have to encourage the development of AI to keep pace with the rest of the world.

PR de Wet Director

[email protected]

VDT Attorneys Inc., Pretoria