Continue reading on DataGuidance with:

Free Member

Limited ArticlesCreate an account to continue accessing select articles, resources, and guidance notes.

Already have an account? Log in

UK: The Data (Use and Access) Bill - what you need to know

The Data (Use and Access) Bill was introduced to the House of Lords of the UK Parliament on October 3, 2024. The Bill aims to amend the UK's data protection regime by including provisions on recognized legitimate interests for lawful processing, automated decision-making, international data transfers, and cookies.

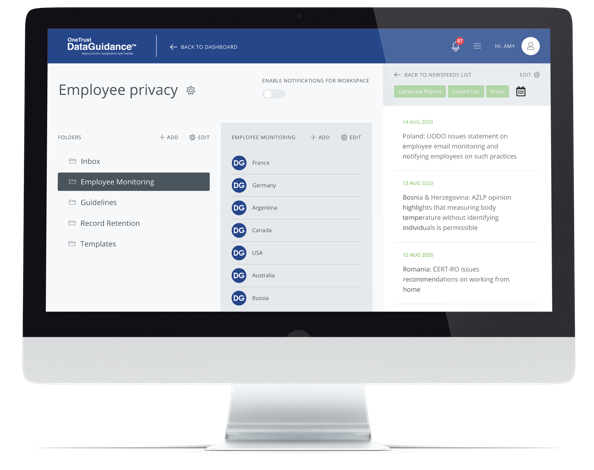

OneTrust DataGuidance Research provides an overview of the Bill, with expert insights by Philip James, Partner at Eversheds Sutherland's Global Privacy & Cybersecurity Group and AI Task Force, and Victoria Hordern, Partner at Taylor Wessing.

Background

A multitude of reforms are proposed under the Bill, including amendments to the UK General Data Protection Regulation (UK GDPR) and the Data Protection Act. Philip further elaborates that ''Whilst we've been waiting, with bated breath, to see how the original Data Protection and Digital Information (DPDI) bill was going to progress following the recent changing of the guard in UK government, post the summer election, the proverbial, Phoenix from the Ashes has taken on a new (and slightly catchier) title. This is in the form of the Bill or 'DUA Bill.' The Bill comprises of over 260 pages. Its key focus, amongst other areas, addresses new provisions and amendments to both UK GDPR and the Data Protection Act:

- Smart Data - defining access rights to customer and business data, whether or not personal information (building on the concept of open banking in financial services to all sectors);

- Digital Verification Services (DVS) - regulating services that use information for identity verification purposes;

- adjustments to the UK data protection laws - i.e., the framework for processing personal information, provisions around automated decision making, special category processing, purpose limitation streamlining data subject access requests (DSARs) - interestingly also around reasons for not responding to a DSAR in the context of manifestly unfounded or excessive requests (Section 53, DPA) and changes to time limits to responding to such requests, and addressing privacy concerns related to electronic communications; and

- ICO Reforms - formally establishing and reinforcing the Information Commission as a regulatory body.''

Victoria provides further insights on the Bill, highlighting that:

"The [Bill] contains considerable overlap with the previous incarnation of UK data protection reform – the [DPDI] bill. For instance, the Government appears to have maintained provisions to establish a framework for access to customer and business data, as well as reforms to the [ICO]. Likewise, the provisions on the UK's approach to international data transfers (which will bring in a new data protection test) and provisions to facilitate the use of data for scientific research remain from the DPDI bill. Furthermore, the identification of certain recognized legitimate interests remains (although without the legitimate interest of democratic engagement), as do the changes to automated decision making. Changes to the PECR have broadly survived so that consent would not be required for analytics or preference cookies.

However, there are certain key differences. For instance, the previous Government's attempt to amend the definition of personal data (always controversial) has been dropped, as has the dilution of [the UK] accountability requirements around data protection officers (DPOs), records of processing activities (ROPAs) and Data Protection Impact Assessments (DPIAs). There also seems to be a new power for the Secretary of State to issue regulations to amend the framework for use of special category data under Article 9 of the UK GDPR. And the ability to argue that a data subject access request is vexatious is no longer included which means controllers will still have to argue that a request is manifestly unfounded or excessive in order to refuse a DSAR."

What are the key changes to the current UK data protection regime?

Recognized legitimate interests

The Bill introduces Annex 1 to the UK GDPR, which lists recognized legitimate interests that can be used as a lawful basis for processing personal data. This includes processing necessary:

- for the disclosure of data needed for a task carried out in the public interest or under the exercise of official authority;

- to safeguard national security, public security, and defense;

- to respond to an emergency such as natural disasters, public health crises, or significant threats to public safety;

- to safeguard a vulnerable individual; or

- to detect, investigate, or prevent crime, or apprehend or prosecute offenders.

Additionally, Philip noted that the ''[Bill] adds further detail around what may be a legitimate interest (amending Article 6 of the UK GDPR):

- processing that is necessary for the purposes of direct marketing;

- intra-group transmission of personal data (whether relating to clients, employees or other individuals) where that is necessary for internal administrative purposes; and

- processing that is necessary for the purposes of ensuring the security of network and information systems.''

Further processing of personal data

The Bill establishes the following circumstances under which the processing of personal data for a new purpose would be considered as compatible with the original purpose for which the data was collected:

- the data subject consents to the processing of personal data for the new purpose and the new purpose is specified, explicit, and legitimate;

- the processing is carried out for the purposes of scientific or historical research, archiving in the public interest, or for statistical purposes; or

- the processing is necessary:

- to protect the vital interests of the data subject or another individual;

- to safeguard a vulnerable individual;

- for the assessment or collection of a tax or duty;

- for complying with an obligation of the controller under law or an order of a court or tribunal; or

- to make a disclosure of personal data to another party if the data is needed for a task that involves the public interest or the exercise of official authority.

Compatible purposes

The Bill states that the following factors should be taken into consideration to determine compatibility with the original purpose:

- any link between the original purpose and the new purpose;

- the context in which the personal data was collected, including the relationship between the data subject and the controller;

- the nature of the processing, including whether it is the processing of special categories of personal data or personal data relating to criminal convictions;

- the possible consequences of the intended processing for data subjects; and

- the existence of appropriate safeguards, such as encryption or pseudonymization.

However, the Bill clarifies that if personal data was originally collected based on the data subject's consent, any further processing for a new purpose is considered compatible with the original purpose only if:

- the data subject gives consent for the processing of personal data for the new purpose;

- the processing is carried out to ensure compliance with the principles relating to the processing of personal data; or

- the processing is for certain listed purposes, including public interest and the controller cannot reasonably obtain the data subject's consent.

Consent

Regarding 'freely' given consent, Philip explains that:

"In particular, there is a proposed clarification around whether consent is freely given; namely, inserting a new Section 40A in the [Data Protection Act], 'When assessing whether consent is freely given, account must be taken of, among other things, whether the provision of a service is conditional on consent to the processing of personal data that is not necessary for the provision of that service.' This seeks to address specific concerns around services making access conditional upon consent (and pay or consent models). This will undoubtedly be a hotly debated area."

Analytics and/or functional cookies used to adjust website appearance

The Bill amends the Privacy and Electronic Communications Regulations (PECR) to expand the types of cookies that do not require a user's explicit consent, to include cookies that:

- are used to gather statistical information;

- change the way the website appears to adapt to user preferences;

- transmit a communication over an electronic communications network; or

- are used to facilitate emergency assistance.

Additionally, the Bill provides more details about how consent for cookies can be obtained, such as through browser settings or using specific applications. Specifically, the Bill clarifies that if consent is given once, it can cover multiple occasions of data storage/access for the same purpose.

Further, the Bill broadens the scope of what it means to store information or access information on a user's terminal equipment to include instigating the storage or access and collecting or monitoring information automatically emitted by the terminal equipment.

Scientific research

The Bill amends Article 4 of the UK GDPR to enable controllers processing data for scientific research purposes to obtain consent to an area of scientific research, where it is not possible to fully identify the purposes for which the personal data will be processed at the time of collection.

The new conditions for valid consent in this regard are:

- consent does not fall within that definition of Article 4(11) of the UK GDPR because (and only because) it is given to the processing of personal data for the purposes of an area of scientific research;

- at the time the consent is sought, it is not possible to fully identify the purposes for which personal data is to be processed;

- seeking consent in relation to the area of scientific research is consistent with generally recognized ethical standards relevant to the area of research; and

- so far as the intended purposes of the processing allow, the data subject is given the opportunity to consent only to processing for part of the research.

Importantly, the definition of scientific research includes research that is publicly or privately funded research, commercial or non-commercial, and includes areas like technological development, fundamental and applied research, and public health studies conducted in the public interest.

Data subject access requests

Controllers would be required to respond to data subject requests within one month of the 'relevant time,' which is defined as the latest of the following:

- when the controller receives the request;

- when the controller receives any further information requested to verify the identity of the data subject; or

- when any fee charged in relation to the request is paid.

The Bill provides that a controller may extend the response time by an additional two months if the requests are complex or if the data subject has made multiple requests. In the event the controller extends the response time, they must notify the data subject of the extension within the initial one-month period and provide reasons for the delay.

However, the Bill clarifies that the data subject is only entitled to such confirmation, personal data, and other information which the controller is able to provide based on a 'reasonable and proportionate search' for the personal data and other information. However, the Bill does not provide further information on what would constitute as 'reasonable and proportionate.'

Further, the Bill allows a controller to request additional information from the data subject to accurately identify the specific information or processing activities being requested. Importantly, the Bill clarifies that the time between when the controller asks for this additional information and when the data subject provides it does not count towards the response timelines.

With regard to the data subject's right to information under Articles 13 and 14 of the UK GDPR, the Bill introduces a new section in the Data Protection Act that provides an exemption for information that is subject to legal professional privilege, which protects all communications between a professional legal advisor and their clients and allows competent authorities to 'neither confirm nor deny' as a response in certain circumstances.

Automated decision-making

The Bill introduces requirements and obligations for decisions that involve the automated processing of personal data. The Bill provides that a decision is based solely on automated processing if there is no meaningful human involvement in making the decision. Whereas a 'significant decision' is defined as one with a legal or similarly significant effect on the data subject.

In determining whether there is meaningful human involvement the decision making, the Bill specifies that a person must consider, among other things, the extent to which the decision is reached by means of profiling.

Under the Bill, significant decisions based on the processing of special categories of data cannot be made solely by automated means unless:

- the decision is based entirely on the processing of personal data to which the data subject has given explicit consent; or

- the decision is necessary for entering into, or performing, a contract between the data subject and a controller, or required or authorized by law, and is necessary for reasons of public interest.

Additionally, the Bill prohibits making a significant decision based solely on automated processing if the processing of personal data for the purposes of the decision is carried out on the basis of public interest or in the exercise of official authority.

For significant decisions based solely on automated processing and based entirely or partly on personal data, the Bill requires controllers to implement safeguards to protect the rights and interests of the data subject. Among other things, these safeguards must:

- provide the data subject with information about the automated decision;

- allow the data subject to make representations about the decision;

- enable the data subject to get human intervention on the part of the controller in relation to such a decision; and

- allow the data subject to contest the decision.

However, the Bill provides for certain exemptions for cases where automated decisions are used in the context of law enforcement for example for legal inquiries, criminal investigations, public security, or national security.

International data transfers

The Bill amends the UK GDPR to introduce a 'data protection test' that empowers the Secretary of State to approve transfers of personal data to a third country or international organization. To meet the data protection test requirements, the standard of protection in the receiving country or organization must ensure that data will continue to be protected at a standard that is not materially lower than the protections provided under UK law.

When determining if the conditions of the data protection test are met, the Bill requires the Secretary of State to consider several factors including:

- the respect for the rule of law and for human rights in the country or by the organization;

- the existence and powers of an authority responsible for enforcing data protection laws in the country or organization;

- the availability of mechanisms for data subjects to seek redress;

- the rules about onward transfers from the third country or organization to other countries or organizations;

- relevant international obligations of the country or organization; and

- the constitution, traditions, and culture of the country or organization.

Regarding the EU adequacy status of the UK for international data transfers, Victoria highlights that "When it comes to the Bill's impact on the UK's adequacy status, the changes the Bill will bring seem unlikely to threaten adequacy. There are certain powers for the Secretary of State to introduce further regulations as part of the bill, but these are not wholesale and the disquiet over the potential of political involvement affecting the role of the UK regulator has subsided."

ICO

Notably, the Bill establishes a body corporate, the Information Commission (the Commission) to replace the existing regulator, the ICO, which is currently structured as a corporation sole. All the functions and powers of the ICO will be transferred to the Commission.

The Bill expands the Commission's powers, specifically related to its ability to issue, interview notices and require reports from data controllers or processors.

The Bill empowers the Commission to issue assessment notices that require a data controller or processor to nominate an approved person to prepare a report on a specified matter. The Commission also has the authority to directly appoint an approved person to prepare the report if it does not approve of the nominated person or the controller or processor does not nominate a person in time.

Additionally, the Bill gives the Commission the power to issue interview notices summoning individuals for questioning as part of an investigation into possible data protection violations or offenses. The Commission may issue interview notices to controllers, processors, their employees, or anyone involved in their management or control.

Digital verification services

The Bill introduces provisions regulating DVS, which are services provided to any extent by means of the internet. Verification services are defined by the Bill as services provided at the request of an individual, consisting of:

- ascertaining or verifying a fact about the individual from information provided otherwise than by the individual; and

- confirming to another person that the fact about the individual has been ascertained or verified from the information so provided.

To regulate DVS, the Bill requires the Secretary of State to publish a DVS trust framework, i.e., a document setting out the rules concerning the provision of a DVS. The Secretary of State would also have to set up a register of DVS providers and would be empowered to issue DVS 'trust marks,' which may be used in the course of providing DVS. The Secretary of State may also prepare and publish one or more supplementary codes to supplement the DVS trust framework.

Conclusion

Overall, the Data (Use and Access) Bill introduces substantial changes to the UK data protection framework. In this regard, Philip opined that ''the decision to introduce the Bill in the House of Lords, rather than the Commons, may be a strategic move to expedite the legislative process. Many of the changes, especially around easing regulatory burdens on SMEs and streamlining DSARs may be welcome. Other amendments which increase the disparity between UK and EU law may, in turn, risk a growing divergence in UK and European data privacy law (which could affect the forthcoming adequacy decision). In contrast, the long-awaited introduction of changes to Smart Data (mirroring the objectives of the EU Data and Data Governance Acts) will bring the UK closer towards fostering open data, innovation and greater competition in the digital economy.''

Victoria further added that ''the Government has publicly emphasised its desire that the new law will improve public services and boost the UK economy. In particular, the intention is to improve the sharing of patients' data within the NHS. The complexity behind the drafting of the Bill, given it amends the existing underlying UK data protection legal framework, doesn't immediately signal how straightforward these political aims will be met as a result of this Bill.''

Therefore, with the new privacy reforms, especially with respect to the restructured regulatory body and new data transfer assessment mechanisms, it remains to be seen how these shifts will influence UK's data protection regime.

Mike Kariuki Privacy Analyst

[email protected]

With comments provided by:

Philip James Partner

[email protected]

Eversheds Sutherland, London

Victoria Hordern Partner

[email protected]

Taylor Wessing, London