Continue reading on DataGuidance with:

Free Member

Limited ArticlesCreate an account to continue accessing select articles, resources, and guidance notes.

Already have an account? Log in

New Zealand: Biometrics under the Privacy Act 2020 - What you need to know

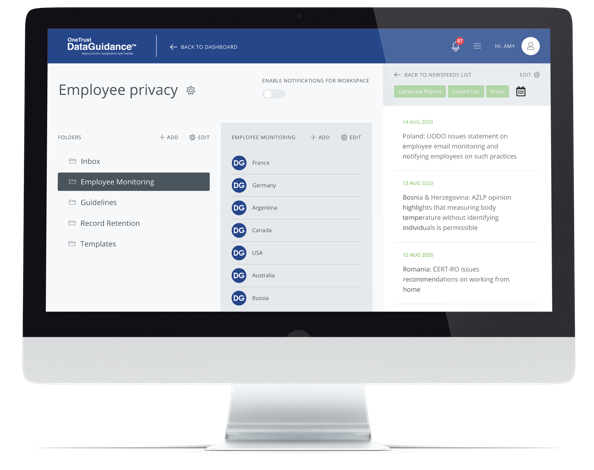

On 6 October 2021, the Office of the Privacy Commissioner ('OPC') released a position paper ('the Paper') setting out its approach to regulating biometrics under the Privacy Act 2020 ('the Act'). As stated by the OPC, the increasing role of biometric technologies leads to calls for greater regulation of biometrics in New Zealand. In addition, the OPC noted that other countries are also considering how best to regulate these technologies, and some have enacted specific regulatory frameworks for biometrics. OneTrust DataGuidance gives an overview of the key information contained in the paper, the OPC's view on processing biometric information, and an outline of how the Act applies to the same.

Background

When releasing the paper, the OPC confirmed that the paper is intended to inform decision-making about biometrics by all agencies covered by the Act, in both the public and private sectors. The paper itself focuses on the use of biometric information in technological systems that use algorithms to conduct automated recognition of individuals, as well as on automated processing of information, as the rapid growth of biometric technologies is creating new and increased privacy risks. Further to this, the OPC confirmed that the paper also aims to:

- inform agencies using or intending to use biometrics about the Act's coverage of biometrics;

- set out OPC's approach to regulation of biometrics under the Act and its expectations of agencies using or proposing to use biometrics; and

- contribute to the wider discussion about whether existing regulatory frameworks adequately address the risks and maintain the benefits of using biometric technologies.

Biometrics: definition, how they are used and how they work

For the purposes of the paper, the OPC defines biometric recognition, or biometrics, as the fully or partially automated recognition of individuals based on biological or behavioural characteristics. The paper further elaborates that there are many types of biometrics using different human characteristics, including a person's face, fingerprints, voice, eyes (iris or retina), signature, hand geometry, gait, keystroke pattern, or odour. The paper states that, generally, there are three broad types of uses for biometrics:

- verification or authentication involves confirming the identity of an individual (is this person who they say they are?), by comparing the individual's biometric characteristic to data held in the system about the individual (a one-to-one comparison);

- identification involves determining the identity of an unknown individual (who is this person?), by comparing the individual's biometric characteristic to data about characteristics of the same type held in the system about many individuals (a one-to-many comparison); and

- categorisation or profiling involves using biometrics to extract information and gain insights about individuals or groups (what type of person is this?).

Furthermore, the paper explains that biometric systems commonly involve three sets of technologies:

- hardware and sensors to capture biometric data - collecting an individual's biometric characteristic, together with other identifying information such as their name, for inclusion in a database is called enrolment;

- databases of enrolled individuals, with their stored biometric characteristics and other identifying information - some biometric databases store biometric templates only and do not retain raw biometrics; and

- software algorithms to create and compare biometric templates - the raw biometric data is converted into a template and, when an agency uses biometrics to verify identity or to identify an unknown person, an algorithm will compare a newly captured (input query) biometric template to a stored (reference) template or templates, to see if a match can be found.

Main concerns

The paper categorises issues regarding biometrics into five main concerns, outlining that privacy risk exists on a spectrum, depending on factors such as the amount of personal information involved, the number of people affected, whether the affected people belong to vulnerable social groups, and whether the biometric system is used to make decisions that could adversely affect individuals and groups.

Sensitivity of biometric information

Biometric information is particularly sensitive, and the paper expands on this by explaining that such information is based on the human body, therefore is intrinsically connected to an individual's identity and personhood. Furthermore, the paper outlines that the misuse of biometric information and collection of such information, by means that are unfair or unreasonably intrusive, therefore not only infringes against personal privacy, but also offends individuals' inherent dignity.

Moreover, the paper adds that the collection and use of biometric information may also have sensitivities that are culturally specific. The paper then clarifies that, for some indigenous groups, an individual's biometric information is directly connected to whakapapa (genealogy), linking the individual to ancestors. Therefore, the paper states that, the use of biometrics may also have a greater impact on some groups than others. In addition, biometric collection and analysis could reveal sensitive secondary information, which are unrelated to the purpose for which the biometric information was collected.

Surveillance and profiling

The paper highlights that the use of some biometric technologies, such as automated facial recognition using real-time CCTV feeds, can create risks of mass surveillance and profiling of individuals. Thus, the paper confirms that, such risks increase when:

- biometric information is collected without the knowledge or authorisation of the individual concerned;

- biometrics are used together with other technologies;

- biometric information is combined with information from other sources;

- decision-making based on use of biometrics is automated, removing human oversight; or

- biometrics are used for purposes that have significant impacts on individuals, such as imposing penalties, conferring benefits, or facilitating access to essential services.

Function creep

'Function creep' is defined by the paper as being when biometric information is collected and held for specific purposes, but subsequently used or disclosed for a different purpose. The paper highlights that an example of function creep would be a government agency collecting biometric information, to enable identity verification for online interaction with the agency, but then using or sharing that information for unrelated law enforcement purposes. Moreover, the paper clarifies that function creep means that people's information may be used in ways that:

- were not originally intended, so appropriate safeguards may not have been provided;

- the individuals concerned are unaware of and have not authorised; and

- increase the risk of surveillance and profiling.

Lack of transparency and control

The paper notes that biometrics can sometimes be used to collect information about people without their knowledge or involvement. Therefore, it clarifies that people's ability to exercise choice and control will also be removed if they are unable to interact with an agency, or access a service, without agreeing to biometric identity verification. In addition, the paper highlights that, the algorithms used in biometrics are generally subject to commercial secrecy. Resultantly, the paper states that lack of transparency about how the algorithms work and their accuracy can make it more difficult to challenge decisions made using biometrics, although this risk can be mitigated through human oversight and manual checking of results.

Accuracy, bias, and discrimination

Lastly, the paper highlights that, depending on the purpose of the biometric system, such errors could result in an innocent individual being investigated for an offence, or an individual being wrongly denied access to a system or place, for example. In this regard, the paper clarifies that biometric technologies may be less accurate for some groups (such as women or ethnic minorities) than others. As such, biometrics are noted as possibly entrenching existing biases, due to the fact that some groups may be over-represented in biometric databases. Therefore, the paper notes that such biases can be particularly harmful when biometrics are used in the imposition of penalties, or the granting of rights or benefits.

How the Privacy Act applies

Biometric information is personal information that the paper confirms is governed by the Act, as biometric information can be used to identify individuals, so it falls within the Act's definition of personal information. Furthermore, the paper highlights that the Act is based on 13 Information Privacy Principles ('IPPs') that set out how agencies must handle personal information, and, in considering the application of the IPPs to biometrics, agencies must take the sensitivity of biometric information into account. The paper highlights two features of the Act as being particularly relevant to regulating biometrics:

- the Act applies to both the public and private sectors, so it regulates the use of biometric information by agencies of all kinds. It also applies to individuals and to overseas agencies that operate in New Zealand;

- the Act is technology-neutral: it does not, for the most part, refer to specific technologies. As a result, the Act can continue to regulate the collection and use of personal information as existing technologies change or as new technologies emerge.

The paper adds that biometric information is specifically referred to in one place in the Act, which is the part that allows agencies to be authorised to verify an individual's identity, by accessing identity information held by another agency. Identity information is defined as including certain types of biometric information by the Act, and, as such, the paper clarifies that, agencies may only be authorised to access identity information for certain specified purposes.

In light of this, the paper sets out a number of aspects to consider with regard to collection and use of biometric information, which include, among other things, that:

- agencies must collect only information necessary for their purposes and should consider whether they can achieve their aim without biometrics;

- collection must be lawful, fair, and not unreasonably intrusive – covert collection will usually only be permissible under a statutory authorisation;

- when biometric information is collected directly from individuals, they must be informed about how and why it is being collected, who will have access to it, and how it will be stored;

- information must be held securely to protect it against loss, unauthorised access, and other forms of misuse;

- the sensitivity of biometric information means that breaches will almost always meet the threshold for mandatory notification; and

- biometric technologies can be less accurate for some groups (such as women or ethnic minorities) – therefore, technologies must be independently tested for New Zealand, and agencies should regularly review biometric systems.

Finally, the paper highlights that, the OPC expects that agencies which include public and private sector agencies will undertake a Privacy Impact Assessment ('PIA') for any projects involving biometrics, and make a strong business case for using biometrics over other approaches. The paper clarifies that these PIAs should consider how privacy risks will be mitigated, the accuracy of the system has been verified, and frameworks beyond the Act. In addition to the standard PIA, the paper confirms that, projects that involve biometrics should also address the following:

- has the sensitivity of biometric information been considered?

- is the proposed use of biometrics targeted and proportionate?

- have perspectives from Te Ao Māori people been considered?

- have relevant stakeholders been consulted?

- will alternatives to biometrics be available?

- how will transparency be provided?

- what human oversight will be used?

Conclusion

The OPC, in its blog post on this topic, confirmed that it believes that careful regulation of the use of facial recognition technology, and other biometric technologies is important. In this regard, the OPC clarified that, in their view, because biometric information is personal information, the Act already regulates the use of biometrics to a significant extent. The position paper itself sets out how the Act applies to biometrics, and how the OPC will exercise our role as regulator. Moreover, the OPC has released a summary resource that highlights some important issues agencies and organisations should consider before using biometric technology.

Furthermore, the OPC has stated that regulation of biometrics needs to address the risks and potential harms of biometrics, while maintaining the benefits of its use. The OPC noted that they recognise that there are issues which do not fit within the framework of the Act, and, therefore, they will continue to monitor the use of biometrics in Aotearoa New Zealand and overseas to see if stronger action is needed. Finally, the OPC has confirmed that they will review their position on this topic in six months, so there will be more opportunities given to participate in this discussion.

Chanelle Nazareth Privacy Analyst

[email protected]