Continue reading on DataGuidance with:

Free Member

Limited ArticlesCreate an account to continue accessing select articles, resources, and guidance notes.

Already have an account? Log in

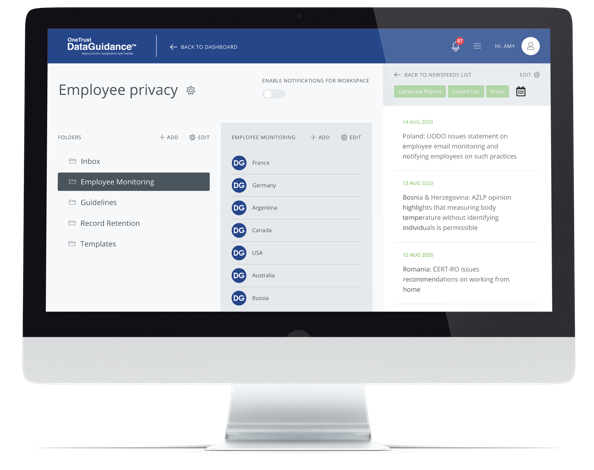

Germany - Employee Monitoring

July 2024

1. Governing Texts

1.1. Legislation relevant to employee monitoring

- The Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (the Charter)

- The General Data Protection Regulation (Regulation (EU) 2016/679) (GDPR)

- The Basic Law for the Federal Republic of Germany (the Constitution)

- The Federal Data Protection Act of 30 June 2017 (implementing the GDPR) (BDSG)

- The Work Constitution Act (BetrVG)

The overall governing principles on the processing of employee data are very similar across Europe. The general principles on the protection of data under EU law are directly applicable in all EU Member States.

The German law specific provision on the processing of employee data, under Section 26 of the BDSG, is under scrutiny at the time of publication. An identical provision in German state law had been submitted to the European Court of Justice (ECJ) by the Administrative Court of Wiesbaden and the ECJ has recently found that this provision does not meet the requirements of its legal basis under Article 88 of the GDPR (which would be, among others, to provide for specific rules in the employment context, such as transparency and the protection of employee data in international corporations). The consequence could be that the provision is inapplicable.

That leaves German employers with the question of whether the processing of employee data can still be based on Section 26 of the BDSG (its most prominent legal basis being the 'requirement' of the data processing for the founding, performance, or ending of the employment contract). In practice, the processing of employee data can be based on the general provisions of Article 6 of the GDPR instead (which most relevant cases of legal basis are, again, the 'requirement' for the performance of the contract or the execution of pre-contractual matters, or the 'legitimate interest' of the employer not being overruled by the interest of the employee).

However, the German legislator is currently (at the time of publication) in the process of drafting a new, more extensive legislation on employee data protection. The plan is to take this as an opportunity to create specific rules for individual processing situations in the employment context. So far, special guarantees seem to be planned in several areas, such as consent, the admissibility of intra-group data transfers, or questions in job interviews.

In addition to these more specific terms for the processing of the data of employees, the following requirements for the processing of (any) data need to be observed, meaning that employees' personal data must be:

- processed lawfully, fairly, and in a transparent manner in relation to the employee as the data subject;

- collected for specified, explicit, and legitimate purposes, and once collected, not be further processed in a way that is incompatible with those purposes;

- adequate, relevant, and limited to what is necessary;

- accurate and kept up to date;

- not kept longer than is necessary; and

- processed in a manner that ensures appropriate security using appropriate technical or organizational measures.

In order to ensure compliance with applicable law, the following steps should be taken:

- A Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) is advisable for a deeper analysis of whether the purpose actually justifies the means and whether the principle of data minimization and the need-to-know principle is properly followed.

- Once a legal analysis has shown that in principle, monitoring is acceptable, it will be required to observe all other provisions of data protection law. For example, data subjects need to be informed about the processing of their personal data (this includes the use of CCTV surveillance). In addition, data retention periods need to be observed.

- Under German law, it is mandatory to appoint a data protection officer (DPO) in all companies that have 20 or more employees who have access to a computer. The DPO at the employer's company must be involved in the analysis and implementation.

- Works council consent needs to be obtained in all companies where a works council has been elected.

- Any data processing activity needs to be registered in the company's register of processing activities under Article 30 of the GDPR).

These rather general terms of what is permissible have been applied by German courts and authorities. The current understanding of what is allowed at the workplace (telephone, CCTV, email monitoring, etc.) will be discussed under each section of the following text.

1.2. Sector-specific legislation relevant to employee monitoring

Germany has little sector-specific employment data protection law. When assessing the legitimacy of employee monitoring in a specific case, courts and the data protection authorities ('DPAs') will primarily assess the case under the general principles of the GDPR and national law.

Exceptions to this rule include the mandatory monitoring of worktime for truck drivers, airline pilots, and under certain collective bargaining agreements.

In addition, since CCTV monitoring of certain public areas such as airports, train stations, etc., is provided for under the BDSG, employees who work there might be impacted.

1.3. Guidelines from supervisory authorities

The German DPAs are organized on a federal level and on a state level for each of the 16 German states. Over the past years, they have jointly issued very general 'short papers' summarizing the legal rules on certain topics, such as Employee Data Privacy, short paper no. 14 (only available in German here) (Short Paper No. 14), and Video Surveillance, short paper no. 15, (only available in German here).

In addition, each of the DPAs issues (bi-)annual reports on their activities. Finally, in specific and highly visible cases, they tend to issue press releases on their activities.

1.4. Notable decisions, i.e. case law or decisions from supervisory authorities

- The Federal Labor Court's (Bundesarbeitsgericht) decision in 2 AZR 153/11 on covert video surveillance (only available in German here)

- The Bundesarbeitsgericht's decision in 2 AZR 546/12 on searching the employee's locker due to theft suspicion (only available in German here)

- The European Court on Human Rights' (ECHR) decision in Case Bărbulescu v. Romania (Application no. 61496/08) on the use of keystroke logging at the workplace

- The Bundesarbeitsgericht's decision in 2 AZR 395/15 on covert CCTV surveillance (only available in German here)

- The Bundesarbeitsgericht's decision in 2 AZR 597/16 on surveillance of an employee by use of a private detective (only available in German here)

- The Bundesarbeitsgericht's decision in 2 AZR 681/16 on keystroke logging at the workplace (only available in German here)

- The Bundesarbeitsgericht's decision in 8 AZR 421/17 on video surveillance (only available in German here)

- The ECHR's decision in Case of López Ribalda and Others v. Spain (Applications nos. 1874/13 and 8567/13) on covert CCTV monitoring in a supermarket for theft detection

- The Hamburg Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information's (HmbBfDI) decision of 01.10.2020 (only available in German here) issuing a fine of €35 million regarding the illicit monitoring of employees' private life and health

- The Bundesarbeitsgericht's decision in 1 ABR 22/21 on the employers' obligation to monitor worktime (only available in German here)

- The Baden-Württemberg State Labor Court's (Landesarbeitsgericht) decision in 12 Sa 56/21 on ongoing unannounced review of business e-mail (only available in German here)

- The Bundesarbeitsgericht's decision in 2 AZR 296/22 on the use of public video surveillance results to prove absence from workplace and worktime fraud (only available in German here)

- The Berlin data protection authority's (the Berlin Commissioner) decision of 02.08.2023, issuing a fine of 215,000 Euro regarding an illicit list evaluating employees during probation and their personal and health situation (only available in German here)

2. Telephone

2.1. What are the rules for recording telephone conversations?

- Article 8 of the Charter

- Articles 5 and 6 of the GDPR

- Articles 1(1), 2(1), and 10 of the Constitution

- Section 26 of the BDSG

- Section 87(1) of the BetrVG

- Section 201 of the German Criminal Code (StGB)

2.2. For which purposes may an employer carry out this type of monitoring?

In principle, a legitimate purpose for the monitoring of telephone conversations is to control the quality of those communications, such as in a call center.

There is little case law on, and few practical cases of the monitoring of telephone communication under German law. The most common case is the monitoring of telephone conversations with external customers, for example, in a telephone hotline. Since covert monitoring of telephone and other spoken conversations is, in principle, a criminal offense, this is usually done based on consent of both the employee and the other party of the call (i.e. the customer). The employee's consent must be obtained in writing, based upon transparent information on the circumstances of the monitoring (see the section on 'Is consent required from an employee? If so, how should consent be sought?' below). For details of obtaining the other party's consent, please see the section on consent from the other party to the call below.

Despite this widespread practice of monitoring telephone conversations (based on consent), it should be noted that in its recent annual report from 2022, the Saxon data protection authority (SächsDSB) has noted that there is no general legitimate interest in monitoring telephone conversations. It has been pointed out that there are less intrusive means to ensure the quality of phone calls.

In addition to these more specific requirements, please refer to the general principles of data processing and the required steps as described above in the section on 'Governing Texts' above.

2.3. Is prior notification/approval with the data protection authority required?

No. As with all types of monitoring under German law, the employer may decide in their own responsibility, based on a legal analysis, possibly a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA), and after involving both the company DPO and the works council.

2.4. Is prior notification/approval/consultation from works' councils required?

Yes. In larger German companies, there is usually a works council in place. Any system that can be used for the monitoring of employee behavior or performance needs to be consulted with the works council before such system can be used. If the works council does not agree on the use of the system, an arbitration procedure needs to be initiated. This means that there is little chance of simply implementing a new software without much discussion and that there may be long negotiations before the software can actually be implemented and used. Works councils are often represented by their own legal counsel and raise typical concerns regarding data protection, transparency, and the actual requirement of the monitoring software. This means that during the negotiations, a much closer look is being taken from a legal perspective than in many companies without a works council.

2.5. Is consent required from employees? If so, how should consent be sought?

Yes, consent should be sought. Employees need to be alerted to the fact that telephone conversations are being monitored. It is advisable to seek their written consent to the fact that this will be part of their role if they work in a telephone hotline and their consent with the resulting data processing. This raises the general issue that consent must be voluntary, and that employees who revoke their consent can no longer be employed in their job role in the call center. This conflict cannot be solved. The monitoring in those cases is part of the job role. One can only argue to what extent it needs to be balanced against the interest of the employee in protecting their privacy from constantly being monitored during their workday. There might be means of mitigation of this infringement of privacy, which are advisable to balance in a DPIA and/or a works council agreement, such as:

- limiting the number of phone calls monitored per employee;

- limiting the possible reactions to unwanted ways of conducting a phone call; and

- limiting the retention period for such recordings, etc.

From a legal point of view, some sources argue that a works council agreement provides a legal basis of monitoring. However, given the fact that illicit listening to conversations is a criminal offense, it is advisable to seek individual consent regardless of a potential works council agreement.

2.6. Is consent required from other parties to the call? If so, how should consent be sought?

Yes, consent is required. Consent of the other party is usually obtained by informing the person before the telephone call that the conversation will be monitored. If the person concerned does not agree to the monitoring, they inform the employee (on behalf of the employer) of this directly at the beginning of the call. Since this cannot be done in writing, which would be the first choice under Articles 4(11) and 7 of the GDPR, consent is usually sought from the other party either as implied consent (by continuing with the phone call after having been informed – but see below, active consent is preferable), or by asking them to type a certain number on the screen of their phone.

According to the recent comments of the SächsDSB in their 2022 annual report, consent must be obtained by provoking an active reaction, such as saying 'Yes' or pressing a number on the phone. This active act helps the employer (being the data processor) to be able to prove compliance with data protection law and have obtained consent.

2.7. Is there a legal requirement for employers to have a written policy in place governing telephone monitoring?

There is no legal obligation to have a specific telephone monitoring policy. However, there is a general legal requirement for information of data subjects under Articles 13 and 14 of the GDPR. In order to be able to prove compliance with that obligation, the information should be done in writing. Such a document might be called a 'policy' or a 'notice.' In companies with a works council, a works council agreement needs to be concluded on any monitoring of employees. Such an agreement is to be made public to all employees and serves as a policy.

2.8. Are there any exemptions to the legal requirements which govern this type of monitoring?

Different rules are applicable for the monitoring of telephone conversations by criminal authorities and in private households. Under Article 2(2)(c) of the GDPR, the law is not applicable to the personal or household activities of individuals.

2.9. What are the retention requirements applicable to data collected through telephone monitoring?

While there is very clear and specific guidance on the retention of CCTV recordings (72 hours, in general), there is little guidance with regard to the retention of telephone recordings. If there is a works council agreement in place, it usually provides for a short retention period, similar to the one recommended for CCTV recordings. If there is no works council agreement in place, it is nevertheless advisable to restrict the retention of telephone recordings to what is necessary for the purpose. If the purpose is monitoring the quality of phone conversations, a typical retention period might be a few workdays to enable the manager to listen to the recordings, raise any concerns, or provide feedback to the employee. After the parties have come to a mutual assessment of the quality of the recording, it must be deleted.

3. CCTV

3.1. What are the rules for CCTV surveillance?

- Article 8 of the Charter

- Articles 1(1) and 2(1) of the Constitution

- Articles 5 and 6 of the GDPR

- Sections 4 and 26 of the BDSG

- Section 87(1)(6) of the BetrVG

The right to video surveillance in the workplace is not explicitly addressed in German statutes so far. It is thought that the new legislation on employee monitoring mentioned in the section on Legislation relevant to employee data protection provides that measures of permanent monitoring should only be possible in exceptional cases and under narrow conditions, an example being the purpose of employee safety and occupational health. Furthermore, clear conditions should be set for open surveillance while covert measures should only be allowed if there is no other possibility of eliminating the concrete suspicion of a criminal act. For now, the general requirements of the GDPR and Section 26 of the BDSG, which supplements the GDPR in the case of data processing in the employment relationship, apply. As mentioned above, Section 26 of the BDSG is currently under scrutiny from the ECJ, but, even if it is inapplicable, in the absence of a valid national provision, the general provision of Article 6 of the GDPR is applied, and the result will remain similar. In addition, the Bundesarbeitsgericht, in its case law (cited above in the section on Notable decisions, i.e. case law or decisions from supervisory authorities and below in the section on For which purposes may an employer carry out this type of monitoring?), has provided guidance on the legal requirements for video surveillance in the workplace.

Open CCTV has a legitimate role to play in helping to maintain a safe and secure environment for all staff and visitors. 'CCTV' means fixed cameras designed to capture and record images of individuals and property. CCTV monitors the exterior of the building and entrances 24 hours a day and this data is continuously recorded. Camera locations need to be chosen to minimize viewing of spaces not relevant to the legitimate purpose of the monitoring and cameras will not be used to record sound.

Staff using surveillance systems will be given appropriate training to ensure they understand and observe the legal requirements related to the processing of personal data.

Open CCTV surveillance needs to be signaled to the public by using symbols and by providing additional information under Articles 13 and 14 of the GDPR on the purposes of processing, recipients, and data retention, etc.

Covert monitoring may only be used at the workplace if there are reasonable grounds to suspect that criminal activity or extremely serious misconduct is taking place and, after suitable consideration, the employer reasonably believes that there is no less intrusive way to address the issue. Only limited numbers of people may be involved in any covert or targeted monitoring.

In all cases of CCTV monitoring, the use of video surveillance for monitoring locations that are part of the most personal area of life of employees (bathroom, locker room, etc.) is prohibited regardless of the purpose.

In addition to the more specific requirements described above and below, please refer to the general principles of data processing and the required steps as described above in the section on Governing texts.

3.2. For which purposes may an employer carry out this type of monitoring?

Typical purposes of CCTV monitoring include the physical security of staff, customers, or passengers, as well as the prevention and detection of theft.

In general, video surveillance in the workplace must be proportionate. It must not represent an excessive burden for the employee and must correspond to the importance of the employer's interest in the information. Also, an important distinction must be made between open and covert CCTV monitoring.

Employees may be openly video monitored as a preventive measure if the monitoring abstractly serves to prevent breaches of duty and the monitoring does not create such psychological pressure to adapt that the persons concerned are significantly inhibited in their freedom to act in a self-determined manner. Constant observation (openly and covertly), which leads to complete technical monitoring of the workplace, is not permitted. On March 28, 2019, the Bundesarbeitsgericht found the open video surveillance by four cameras in a lottery retailer, in general, to be permissible as the employee had knowledge of being monitored by the cameras. But it would have to be assumed impermissible due to psychological pressure if there had been a complete, permanent, and very detailed recording of the employee's behavior during their entire working hours, so that they had to assume that their every movement was monitored. In this case, there would have been no possibility – comparable to the situation of covert surveillance – to exercise their right to privacy in an unguarded and undisturbed manner.

Most recently, on June 27, 2023, the Bundesarbeitsgericht confirmed that the use of open CCTV footage from cameras installed at the gate of the employer's premises is permissible. The case was about an employee who had claimed more worktime than the CCTV recordings at the front gate of the employer's premises confirmed. The employee had argued, among other aspects, that the employer had kept the recordings for several months, rather than the 72 hours permissible under German law. However, the Bundesarbeitsgericht stated that this breach of data retention rules did not make the evidence inadmissible.

Covert CCTV surveillance of an employee remains possible only under very strict conditions. It is permissible if there is a concrete suspicion of a criminal act or other serious misconduct to the detriment of the employer, less drastic means of clarifying the suspicion have been exhausted, covert video surveillance is practically the only remaining option, and it is not disproportionate in comparison to the employee's general interest in retaining their privacy. The Bundesarbeitsgericht confirmed this in many cases, for example, in a case concerning a dismissal on suspicion of covert CCTV surveillance on March 27, 2003. The employee had argued that the CCTV recordings could not be used as evidence against them because they had been made in a disproportionate and thus inadmissible manner by encroaching on their right to privacy. Yet, the Bundesarbeitsgericht declared the evidence admissible as the encroachment on the right of privacy was justified. All named requirements were met.

Covert CCTV surveillance must be the last resort available to clarify the criminal act or misconduct, as stated by the Bundesarbeitsgericht on June 29, 2017. The case concerned sufficient grounds for suspicion of unlawful competition activity and of feigning incapacity to work for this purpose, which would constitute serious misconduct. Less restrictive measures of clarifying the suspicion must have been exhausted without results. Also, the suspicion must be directed against a group of employees that can be limited at least spatially and functionally.

3.3. Is prior notification/approval with the data protection authority required?

No. As with all means of monitoring under German law, the employer may decide in their own responsibility, based on a legal analysis, possibly a DPIA, and after involving both the company DPO and the works council.

3.4. Is prior notification/approval/consultation from works' councils required?

Yes. In larger German companies, there is usually a works council in place. Any system that can be used for the monitoring of employee behavior or performance needs to be consulted with the works council before such system can be used. If the works council does not agree on the use of the system, an arbitration procedure needs to be initiated. This means that there is little chance of simply implementing a new software without much discussion and that there may be long negotiations before the software can actually be implemented and used. Works councils are often represented by their own legal counsel and raise typical concerns regarding data protection, transparency, and the actual requirement of the monitoring software. This means that during the negotiations, a much closer look is being taken from a legal perspective than in many companies without a works council.

3.5. Is consent required from employees? If so, how should consent be sought?

In principle, no. CCTV monitoring, under German law, was so far based on being required for the performance of the employment contract. Section 26 of the BDSG does not require a 'legitimate interest' as a legal basis in an employment context, unlike the legal rules in most other EU countries. Now, with Section 26 of the BDSG being under the scrutiny of the ECJ and possibly invalid, it could be argued that the employer's 'legitimate interest,' as provided under Article 6(f) of the GDPR, is back as a possible basis for CCTV monitoring. That remains to be seen. In the meanwhile, it is advisable to follow the previous argumentation of CCTV monitoring being required for the performance, and to observe the general requirements listed under the section on 'For which purposes may an employer carry out this type of monitoring? above.

Consent of the employee may constitute an additional justification for open video surveillance. However, the practical significance is limited. Consent must be voluntary and revocable. If the employee works in a place where ongoing open CCTV monitoring is required, the consequence of revoked consent would be to end the employment. The situation is similar to what is stated above for the monitoring of telephone conversations being part of some job roles. The conflict cannot be solved, but it can be mitigated as mentioned above in the section on 'Is consent required from employee? If so, how should consent be sought?' Employees should be well informed about the CCTV monitoring in a notice or policy and that document should be counter-signed as proof of receipt.

In cases of covert CCTV surveillance, for practical reasons, consent is usually not an option.

3.6. Is there a legal requirement for employers to have a written policy in place governing CCTV surveillance?

There is no specific legal obligation to have a CCTV monitoring policy. But there is a general legal requirement for the information of data subjects under Articles 13 and 14 of the GDPR and there is a general obligation to be transparent when processing personal data. The notification requirement under Section 4 of the BDSG also refers to Articles 13 and 14 of the GDPR. In order to be able to prove compliance with those obligations, the information should be done in writing. In addition, electronic transmission could be considered. Such a document might be called a 'policy' or a 'notice.' In companies with a works council, a works council agreement needs to be concluded on any monitoring of employees. Such an agreement is to be made public to all employees and serves as a policy.

3.7. Are there any exemptions?

As mentioned above, there are different rules in place for monitoring by criminal authorities, and for private households.

3.8. What are the retention requirements applicable to data collected through CCTV surveillance?

The general rule for the retention of CCTV footing is very clear. It is to be kept no longer than 72 hours. In the event of an investigation, litigation, or court proceedings (or if these are anticipated), personal data may be retained for the duration of such investigation, litigation, or court proceedings.

This is the consensus of German DPAs (such as in Short Paper No. 14) and of legal commentaries. Recently, the Bundesarbeitsgericht has in principle confirmed the 72-hour rule, even if in the particular case, evidence out of CCTV recordings kept for (much) longer than 72 hours was still admissible in court (decision of June 6, 2023). This is, among other aspects, because German civil law (as opposed to criminal law) in general does not work with evidence becoming inadmissible as a sanction for breaches of procedural law.

To be clear, this civil law decision does not mean that the employer is protected against a fine from the local DPA. There have been several cases in the past years of large fines being awarded to German employers and other data processors based on a breach of data retention rules.

4. Email

4.1. What are the rules regarding monitoring of employees' emails?

- Article 8 of the Charter

- Articles 5 and 6 of the GDPR

- Articles 1(1) and 2(1) of the Constitution

- Sections 26 of the BDSG

- Section 88 of the Telecommunications Act, 2021 (only available in German here) (TKG)

- Section 87(1)(6) of the BetrVG

Regarding the monitoring of emails under German law, an important distinction must be made as to whether the employer has permitted private use of the business email box and the company's internet. If private use of emails and the internet is permitted or tolerated, it has been under dispute for a long time whether the current prevailing view is that the employer becomes a telecommunications service provider vis-à-vis its employees within the meaning of the Federal Act on the Regulation of Data Protection and Privacy in Telecommunications and Telemedia, 2021 (only available in German here) (TTDSG). If so, the employer would be obligated to maintain telecommunications secrecy under Section 3(1) of the TTDSG. This considerably restricts the employer's monitoring options. The stricter standards for monitoring private communications also apply to business emails. The employer is thus prohibited from monitoring and logging IT use. The employer may only obtain knowledge of the content and circumstances of the telecommunications to the extent necessary for the provision of the telecommunications services, e.g., for billing purposes. If the employee has left the company or is permanently ill and the employer requires access to the employee's email inbox for operational reasons, the employer may be prevented from doing so due to the permitted use of this inbox for private communications. A permissible review of the content of private emails can only be carried out with the consent of the employee or in extreme exceptional cases, e.g., if a criminal offense is suspected.

In the legal literature, there is no consensus, whereas the majority of case law seems to be against it (e.g. Regional Labor Court of Berlin-Brandenburg, the decision of January 14, 2016 - 5 Sa 657/15 and Regional Labor Court of Hamm (Westphalia), the decision of and July 10, 2012 - 14 Sa 1711/10). The courts reason that there is no business-like provision of telecommunications services within the meaning of the TTDSG if the employer allows its employees to use the company computers privately. Either way, it is absolutely advisable for employers to not allow private use at all. Otherwise, there is a great risk that access to business data will be made unnecessarily difficult.

4.2. For which purposes may an employer carry out this type of monitoring?

Whether emails can be monitored depends on a number of circumstances:

- if private use of company IT and the company email address has been prohibited (as mentioned above in the section on 'What are the rules regarding monitoring of employees' emails?');

- if the monitoring is conducted with regard to business or private emails;

- if this monitoring is done in an open or covert manner;

- if this takes place during the ongoing employment relationship or after the employee has left;

- if it is a random monitoring or ongoing and constant surveillance of the employee; and

- the reasons for the monitoring.

As mentioned above, if private use of the business email box and the company internet is prohibited, the employer may monitor these systems comprehensively to check whether the employee has used them only for business purposes or – impermissibly – for private purposes. In particular, the recording of the internet address as well as the content of the transmitted data is therefore required. Similarly, the European Court of Human Rights ('ECHR') has also ruled (on January 1, 2016) that the employer may check whether the use is in fact for official purposes if the private use is prohibited.

However, as a general rule, it is required that the employer must inform the employees comprehensively about the monitoring that is taking place; according to Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights, there are limits to the monitoring itself. A fair balance between the employee's right to privacy and their employer's interests is necessary. The decision of the ECHR makes regular or ongoing random checks or specific, occasion-related comprehensive checks of the use of company email systems and internet access for violations of a prohibition on private use compatible with German law. The content of business emails and company internet may also be monitored. Business emails are part of the company's business correspondence, to which the employer has unrestricted access. Continuous technical monitoring of the employee's email and internet communication is inadmissible for reasons of privacy protection, because it would create a permanent pressure. However, this correctly excludes only continuous secret reading or evaluation, not technical automated recording, and software-supported content checking.

On the other hand, if private use of the business email box and the company internet is permitted or tolerated, the monitoring is significantly restricted (as already mentioned above, in the section on 'What are the rules regarding monitoring of employees' emails?'). A permissible review of the content of private emails can then only be carried out with the consent of the employee or in extreme exceptional cases, e.g., if a criminal offense is suspected. Otherwise, only the examination of connection data (date, time, duration, participants, etc.) is permissible.

Besides, typical purposes of email monitoring are compliance measures, to determine whether legal regulations are being adhered to. The monitoring of incoming and outgoing emails is also a typical side effect of a cybersecurity policy, according to which all traffic needs to be monitored and content needs to be inspected in order to identify threats to information security (e.g., virus attacks). The content of emails may also be investigated when an employee is absent from work to maintain the normal course of business.

After departure from employment, the employer should block (deactivate) email accounts of ex-employees at the latest at the time of termination; the automatic forwarding of emails received after termination is rather problematic. Before the email account will be deactivated, the employee should be obliged to sort their account and to delete or save private emails elsewhere. In this case, access to or a 'snapshot' of the remaining business emails received before termination is unproblematic after the employee has left. At best, it should be able to prove this request/obligation. Even if private use will be prohibited in the future, the employee should be obliged to delete any private emails, since private emails can also have been received by mistake.

In addition to these more specific requirements, please refer to the general principles of data processing and the required steps as described above in the section on general texts above.

4.3. Is prior notification/approval with the data protection authority required?

No. The employer may decide in their own responsibility, based on a legal analysis, possibly a DPIA, and after involving both the company DPO and the works council.

4.4. Is notification/approval/consultation with works' council required?

Yes. In larger German companies, there is usually a works council in place. Any system that can be used for the monitoring of employee behavior or performance needs to be consulted with the works council before such system can be used. If the works council does not agree on the use of the system, an arbitration procedure needs to be initiated. This means that there is little chance of simply implementing a new software without much discussion and that there may be long negotiations before the software can actually be implemented and used. Works councils are often represented by their own legal counsel and raise typical concerns regarding data protection, transparency, and the actual requirement of the monitoring software. This means that during the negotiations, a much closer look is being taken from a legal perspective than in many companies without a works council.

In contrast, the employer's ban on using the company internet and email for private purposes is generally not considered to be subject to the works council's right of co-determination. But such a rule is usually part of a larger set of rules regarding the permissible use of company IT and is therefore typically part of a works council agreement.

4.5. Is consent required from employees? If so, how should consent be sought?

Usually, consent by itself is not an option to create a legal basis for the monitoring of emails. To the extent that email monitoring is necessary for the performance of the employment contract, no consent is required. If the monitoring of emails is not required, it is difficult to imagine basing it on consent. The use of email, if it is part of the job role, cannot be replaced by an alternative.

4.6. Is there a legal requirement for employers to have a written policy in place governing email monitoring?

There is no specific legal obligation to have a specific email monitoring policy. But there is a general legal requirement for the information of data subjects under Articles 13 and 14 of the GDPR and there is a general obligation to be transparent when processing personal data. In order to be able to prove compliance with that obligation, the information should be done in writing. Such a document might be called a 'policy' or a 'notice.' In companies with a works council, a works council agreement needs to be concluded on any monitoring of employees. Such an agreement is to be made public to all employees and serves as a policy.

However, the employer should expressly prohibit its employees from using the business email system or company internet for private purposes as part of a company policy. As a consequence, the employer does not restrict its monitoring options and does not expose itself to any criminal risk in the event of necessary telecommunications checks. Conversely, if private use is permitted, clear and documented rules are also required for this. This prohibition is usually stated in a policy or a notice on the use of company IT.

4.7. Are there any exemptions to the legal requirements which govern this type of monitoring?

As with the other types of monitoring, there are different rules in place for criminal authorities, and for private households.

4.8. What are the retention requirements applicable to data collected through email monitoring?

The answer to this question depends on the circumstances of the case. If data is collected through monitoring that is addressed to a particular employee and no suspicion of any misbehavior is confirmed, the data obtained through monitoring should be deleted as soon as it is no longer needed (since the investigation is closed).

However, outside of the monitoring of single employees, business emails regarding contracts should at least be kept for the duration of exclusion and limitation periods. The general exclusion and limitation period under German law is three years, ending on December 31 of the third year after the claim has arisen.

A six-year or ten-year retention period from the Commercial Code (HGB) should be observed for business emails regarding business transactions that are relevant for the company's annual report.

5. Biometrics

5.1. What are the rules regarding biometric monitoring?

- Article 8 of the Charter

- Articles 5, 6, and 9 of the GDPR

- Articles 1(1) and 2(1) of the Constitution

- Section 26 of the BDSG

- Section 88 of the TKG

- Section 87(1)(6) of the BetrVG

Biometric monitoring is the processing of personal data which allow for a clear identification of the employee. Examples of biometric data that might be relevant in the workplace include the use of fingerprints, biometric photos, or retina scanners. Biometric data is a special category of data under Article 9 of the GDPR. The processing of such data is, in principle, prohibited, but there is a list of exemptions to the prohibition. The contractual relationship between the employer and the employee is not viewed as a sufficiently legitimate basis for the processing of this type of data. The most relevant exceptions to the prohibition from processing biometric data in the employment context are:

- that the individual has given explicit consent;

- it is necessary for the exercise of specific rights of the employer; or

- the processing is required for the fulfillment of legal obligations arising from labor law, social security law, and social protection law, and there is no reason to assume that the data subject's legitimate interest in the exclusion of processing outweighs this interest.

In all cases of permissible biometric monitoring, appropriate and specific safeguards for the fundamental rights and interests of the employees are required.

In addition to these more specific requirements, please refer to the general principles of data processing and the required steps as described above in the section on general texts above.

5.2. For which purposes may an employer carry out this type of monitoring?

In general, cases of legitimate biometric monitoring at the workplace are rare. As a rule, a less intrusive option should be explored. Mere practical considerations are not a sufficient justification for this kind of monitoring. Biometric monitoring is particularly relevant in the area of access control or authentication to areas of high security. By completely dispensing with badges and passwords, which can be lost, passed on, or stolen, a high level of security can be achieved because only the authorized person can enter the relevant area or system. The most common case is the use of iris scans or fingerprint systems to secure access to highly sensitive areas. Other examples of biometric features include hand and facial geometry as well as retina scans and voice characteristics.

A recent decision of the Italian data protection authority (Garante) of June 1, 2023, is worth mentioning in this context. The employer in this case had used multiple forms of monitoring on its employees, including the use of an alarm system with fingerprints, continuous GPS tracking of its staff, as well as surveillance of remote-activated video and sound. The Garante stated that this use of fingerprints and hence the processing of biometric data and the other ways of remote monitoring are not required and awarded a fine of €20,000. While this is not directly applicable to Germany, it shows the general attitude of European DPAs with regard to covert and extensive monitoring of employees.

More controversial, biometric monitoring might be carried out for the purpose of recording working time. For this, fingerprints might be used, which some sources judge as being proportionate with regard to the protection of health intended thereby, as long as the fingerprint data deposited for this purpose is sufficiently secured and if an alternative means of identifying oneself is offered to the employee, such use of fingerprints might be based on their (informed, explicit, and written) consent. If consent is then revoked, employees can use alternative means of identification.

Inadvertent biometric monitoring might take place in cases where biological patterns are being saved without the purpose of monitoring employee behavior, for example, when the employee's passport with a biometric picture is being saved in the company's travel booking system. With biometric information becoming increasingly common for identification purposes in the private environment, employers need to make sure they do not use that data unless required.

5.3. Is prior notification/approval with the data protection authority required?

No. The employer may decide their own responsibility, based on a legal analysis, such as a DPIA, and after involving both the company DPO and the works council. Due to the sensitivity of biometric data, a consultation procedure with the DPA in accordance with Article 36 of the GDPR and Section 67 of the BDSG might also be carried out in order to avoid not inconsiderable legality risks and associated subsequent sanctions.

5.4. Is notification/approval/consultation with works' council required?

Yes. In larger German companies, there is usually a works council in place. Any system that can be used for the monitoring of employee behavior or performance needs to be consulted with the works council before such system can be used. If the works council does not agree on the use of the system, an arbitration procedure needs to be initiated. This means that there is little chance of simply implementing a new software without much discussion and that there may be long negotiations before the software can be implemented and used. Works councils are often represented by their own legal counsel and raise typical concerns regarding data protection, transparency, and the actual requirement of the monitoring software. This means that during the negotiations, a much closer look is being taken from a legal perspective than in many companies without a works council.

5.5. Is consent required from employees? If so, how should consent be sought?

That depends. Biometric monitoring might also be based on being strictly required for the performance of the employment relationship (for example, in a high-security environment). Consent is another possible justification for biometric data processing if an alternative option can be provided. So, for example, an alternative to time logging by fingerprint would be to provide employees with a badge and/or password so they can be identified using two-factor identification.

Consent to the processing of biometric data, in order to be considered valid, requires that the consent explicitly refers to the biometric data and that the specific purposes of the data processing (in particular identification) are stated (Article 9(2) of the GDPR and Section 26(3) of the BDSG). In addition, the sensitivity of the biometric data should be pointed out separately. To be able to prove effective consent, it should be obtained in written form.

5.6. Is there a legal requirement for employers to have a written policy in place governing biometric monitoring?

There is no specific legal obligation to have a specific biometric data monitoring policy. However, there is a general legal requirement for the information of data subjects under Articles 13 and 14 of the GDPR and there is a general obligation to be transparent when processing personal data. In order to be able to prove compliance with those obligations, the information should be done in writing. Such a document might be called a 'policy' or a 'notice.' In companies with a works council, a works council agreement needs to be concluded on any monitoring of employees. Such an agreement is to be made public to all employees and serves as a policy.

5.7. Are there any exemptions to the legal requirements which govern this type of monitoring?

As with all types of monitoring, special exceptions apply to the monitoring by criminal authorities. Also, the rules on data protection are not applicable in a private household.

5.8. What are the retention requirements applicable to data collected for biometric monitoring?

In principle, the data collected from biometric monitoring must be deleted immediately if it is no longer required to achieve the purpose or if the employee's interests merit protection against further storage.

6. Device Monitoring

6.1. What are the rules regarding company-owned device monitoring?

- Article 8 of the Charter

- Articles 5, 6, and 9 of the GDPR

- Articles 1(1) and 2(1) of the Constitution

- Section 26 of the BDSG

- Section 88 of the TKG

- Section 87(1)(6) of the BetrVG

Company-owned device monitoring includes the following categories of monitoring being performed from desktops and company-issued laptops or mobile phones and tablets:

- keystroke logging;

- productivity monitoring software including a live view of the screen;

- internet and intranet use monitoring; and

- location monitoring (also called GPS tracking).

As a general rule, without a specific reason for their use, most of these systems cannot be used in Germany simply to observe employees and prevent them from being sidetracked. Cases of use of these types of monitoring are rare in practice and are usually either based on a specific justification or are cases of illegal monitoring.

In addition to these more specific requirements, please refer to the general principles of data processing and the required steps as described above in the section on general texts above.

6.2. For which purposes may an employer carry out this type of monitoring?

As stated above, in principle, these types of monitoring are generally not legitimate. For example, a keystroke logging software that had been installed on an employee's laptop to find out if the employee was busy with tasks that were not related to their job was considered to be illegal by the Bundesarbeitsgericht in a decision from July 27, 2017.

A similar decision with regard to keystroke logging has been made by the ECHR in Bărbulescu. In this case, the Romanian courts had found that the employer had been entitled to monitor the instant messaging accounts of an employee (who had spent extensive time chatting with both their brother and fiancée), which led to their dismissal for breach of the IT policy. The court held that the employee's right to privacy had been breached by the employer's covert monitoring. Its conclusion was that the Romanian courts had failed to strike a fair balance between the opposing interests.

Software that has the specific purpose to monitor an employee's productivity is hardly heard of in the German market, and there is no case law to be found so far. While there are some vendors of such 'productivity monitoring' systems, it would be difficult to argue that such a system is necessary and the least intrusive means to monitor employees.

However, there are systems that have a different purpose, but the side effect of constantly monitoring employees' behavior including their emails or internet use, such as an AI-powered time tracking software. Such software constantly monitors how the employees are spending their day, what emails they are writing to whom, and what browser windows are open, then it creates a draft narrative for the daily time tracking detailing client, project, and work hours. There is no case law so far on the use of such software. But with the application of general principles of privacy protection at the workplace, it seems advisable to seek prior consent from the employees before deploying such a system and to offer an alternative (in the case of an AI-powered time logging system for lawyers and other timekeepers, manual time recording would provide such an alternative).

Another exception to the general prohibition is the implementation of a cybersecurity system. Monitoring of internet use and of all incoming and outgoing data traffic is an unavoidable consequence, even a necessity for any cybersecurity system. In principle, this is permissible as the cybersecurity software cannot function otherwise. The vast amount of data that need to be processed is being balanced by strict rules on what the data may be used for, and by allowing only a very small circle of persons authorized to access such data.

Ongoing location or GPS tracking is generally not permissible. The situation may be different, however, when the timely provision of location-based services such as cab and limousine rides, food and grocery deliveries or other deliveries of daily necessities, the deployment of employees, often transport or delivery drivers, can only be controlled sensibly and efficiently with precise recording of their respective location. In this case, GPS tracking does not primarily serve to monitor the work performance, but rather to logistically control the provision of the work performance or the service to the customer. This changes the proportionality assessment and usually allows GPS tracking of employees during working hours if the use of the data is limited to the purpose of providing the work. GPS tracking would thus usually be permissible to manage a fleet of cars where the exact location must be known in order for other services to function properly, such as the dispatch of ambulances or refuse collection trucks.

6.3. Is prior notification/approval with the data protection authority required?

No. The employer may decide their own responsibility, based on a legal analysis, in case of device monitoring certainly a DPIA, and after involving both the company DPO and the works council.

6.4. Is notification/approval/consultation with works' council required?

Yes. In larger German companies, there is usually a works council in place. Any system that can be used for the monitoring of employee behavior or performance needs to be consulted with the works council before such system can be used. If the works council does not agree on the use of the system, an arbitration procedure needs to be initiated. This means that there is little chance of simply implementing a new software without much discussion and that there may be long negotiations before the software can be implemented and used. Works councils are often represented by their own legal counsel and raise typical concerns regarding data protection, transparency, and the actual requirement of the monitoring software. This means that during the negotiations, a much closer look is being taken from a legal perspective than in many companies without a works council.

6.5. Is consent required from employees? If so, how should consent be sought?

It is not possible to justify illicit, ongoing, and covert processing of employee data with very general data processing consent which might have been obtained in advance. In general, this very intrusive type of processing of employee data must be required for the performance of the employment relationship. Nevertheless, employees should be well informed about the necessity and about the details of such data processing (see the section on requirements for employers to have a written policy in place governing company-owned device monitoring).

6.6. Is there a legal requirement for employers to have a written policy in place governing company-owned device monitoring?

There is no specific legal obligation to have a specific company device monitoring policy. However, there is a general legal requirement for the information of data subjects under Articles 13 and 14 of the GDPR and there is a general obligation to be transparent when processing personal data. This requirement to be transparent is even more crucial in cases where unexpected monitoring takes place at the workplace, such as monitoring with the use of devices. In order to be able to prove compliance with those obligations, the information should be done in writing. Such a document might be called a 'policy' or a 'notice.' In companies with a works council, a works council agreement needs to be concluded on any monitoring of employees. Such an agreement is to be made public to all employees and serves as a policy.

6.7. Are there any exemptions to the legal requirements which govern this type of monitoring?

Again, official authorities are governed by different rules if they process personal data as part of a criminal investigation. Also, as with all rules on data protection, they are not applicable to the processing by private households.

6.8. What are the retention requirements applicable to data collected from the company-owned devices?

As opposed to the very strict and clear rule on the retention of CCTV footing (72 hours unless there is an ongoing investigation), there is no clear guidance. So, in the absence of clear time frames, data should only be retained as long as strictly required. If nothing comes up within a few days, data should be deleted. If covert monitoring is required as part of an investigation where there are no less intrusive means, the data can be retained until the investigation is – swiftly – closed.

7. Covert Surveillance

Similar to the use of covert CCTV monitoring, covert surveillance of the use of company-owned devices can only be carried out if there is a clear suspicion of criminal behavior or a breach of contract if this suspicion can be demonstrated based on facts and if there are no less intrusive means of investigating. Even then, additional precautions must be taken such as:

- limiting the number of persons monitored;

- limiting the time frame of monitoring;

- limiting the number of devices monitored;

- involving the works council (if elected) with prior information (without mentioning the employee's name, if feasible); and

- informing the investigated individual immediately after the investigation is terminated.

8. Employees' Access Rights

Under Article 15 of the GDPR, employees are entitled to receive information about the categories of personal data which are being saved about them and to receive a copy of the actual data. The ECJ recently, on May 4, 2023, decided that 'copy' means an actual facsimile of the data which is being stored, not just a general summary of data.

Also, the ECJ has recently, on January 12, 2023, decided that data subjects (including employees) must be provided not just with the categories of data recipients, but with the names of the data recipients in the specific case. In an employment context, that might involve external payroll providers, IT services, or any parent company processing the employee data on behalf of its affiliate company.

In addition, under German law, employees are entitled to review their personnel files. While this law has rarely been relevant in legal practice, the data subject access request out of Article 15 of the GDPR is increasingly popular and being used out of actual interest in the data and just as often for presumably tactical reasons. If employers do not have a process in place to quickly respond to these requests, they can cause quite a lot of work and trouble.

9. Penalties

A breach of the GDPR can result in serious financial penalties (Article 83 of the GDPR): fines up to €20 million or 4% of a company's total global turnover in the previous fiscal year (whichever is higher) for the most serious breaches. The sanctioning regime is harmonized across the EU.

So far, there have been a few cases of German DPAs handing out fines in cases of employee monitoring. Most cases of fines address the processing of customer data, website user data, etc. The two cases worth mentioning were the Hamburg Commissioner for Data Protection and Freedom of Information (HmbBfDI) in the case against H&M Hennes & Mauritz (only available in German here) on September 30, 2020, with a fine of €35 million, and the recent case of the Humboldt Forum with a fine of €26,000. In both cases, the employer – or the managers in place - had saved information on their employee's personal life, health, family situation, and general fitness to work in a clandestine list.

The GDPR also provides for other types of remedies. Those include rights to lodge complaints with a supervisory authority, to effective judicial remedies, and to receive compensation of damages (Article 82 of the GDPR). The GDPR provides for EU Member States to enact legislation on other penalties. In Germany, penalties can also arise from the employee's right to information. The employee can demand the return of all personal data stored; if this demand is not met (or not fully met), a fine may be imposed.

Supervisory authorities (referred to as DPAs) are vested with investigative and corrective powers. The corrective powers range from issuing orders, warnings, and reprimands, to the imposition of (temporary or permanent) bans on processing activities, as well as fines.